Commemorating the 501st anniversary of Martin Luther’s 95 theses

BY W. THOMAS SMITH JR.

[An abridged version of this story was published, Oct. 2017, in Columbia Metropolitan magazine.]

FIVE HUNDRED AND ONE YEARS AGO THIS MONTH (specifically October 31, 1517), a little-known priest and university professor by the name of Martin Luther made his way past the gathering crowd toward the large double doors of All Saints Church in the border town of Wittenberg, Saxony – then a Germanic state in the Holy Roman Empire. In one hand, he held a lengthy hand-written list of 95 points of contention he hoped to debate about the church he loved. In the other, a hammer.

At the door, people were milling about as usual, though the crowds were larger than normal. It was the eve of All Saints Day or “All Hallows Eve,” and Wittenberg’s citizenry as well as those living in the countryside were converging on the town, specifically around the church. All were preparing for the big Roman Catholic feast day to follow.

Posting announcements and various other notices and bulletins on the church doors was not uncommon in those days, especially from professors, like Luther, who were teaching at nearby Wittenberg University. And Luther was surely aware that larger crowds, like those on October 31-November 1, meant a larger audience.

Luther quickly walked up to the church entrance and began nailing his list to the door. Bam! Bam! Bam! Heads turned toward him.

Luther quickly walked up to the church entrance and began nailing his list to the door. Bam! Bam! Bam! Heads turned toward him.

Luther’s intent with the list, officially his “95 theses,” wasn’t to start a revolution. It was aimed at stirring debate. He wanted to get people talking and thinking about at least a partial reforming of some of the extra-Biblical church traditions and church-instituted teachings and activities that he believed had no basis in Scripture. He feared that those traditions and teachings lulled Christians into wrong-headed beliefs that salvation could be achieved through good works or, worse, church-sanctioned indulgences (essentially purchased “merit”).

In Luther’s way of thinking (and in the hearts of every Protestant Christian since), salvation was and is achieved by “faith alone,” with good works being the fruit of that faith as opposed to a means by which salvation is achieved.

Luther loved God. He loved the church. He wanted to please God, and he struggled mightily with the fact that he believed he would never be able to achieve righteousness through his daily strivings to please God. His eyes, however, were opened when he read in Romans 1, “The righteous shall live by faith.” Therein lies the heart of Luther’s theology.

Word quickly spread of Luther’s 95 theses, aided by Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary new moveable-type printing press. The list went viral so to speak. The church recognized the gravity of it. It had the potential of changing everything (it ultimately did). Luther’s very life was now in danger.

For the next three years, Luther was urged to recant his statements, the “95” and his other writings and teachings. He refused. The church was fast running out of options as to what might be done about this brash German troublemaker. In January 1521, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X. By mid-April, Luther found himself answering allegations of heresy at the now-famous Diet of Worms (an assembly of princes and prelates overseen by the Holy Roman Emperor) with the strong possibility that the 37-year-old excommunicant would be burned at the stake.

Luther was, again, given an opportunity to save himself. All he had to do was “recant,” and all would be forgiven.

He responded, “My conscience is captive to the Word of God. Thus I cannot and will not recant, because acting against one’s conscience is neither safe nor sound. Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me.”

Luther was swiftly branded an outlaw. Execution seemed imminent. But on the return trip to Wittenberg, he was snatched in the dead of night and spirited away by a band of horsemen who turned out to be friendlies. Acting on the command of Prince Frederick the Wise, a staunch defender of Luther, the horsemen delivered the ex-priest to Wartburg Castle near the town of Eisenach. There Luther spent nearly a year in hiding, where he translated the New Testament from Greek into his native German.

It was also at Wartburg where Luther experienced his most legendary encounter with the devil. Luther was a deeply spiritual man, and this spirituality – though a blessing – also led to his being tormented, as he believed, by “the enemy” (the devil). It might even be argued that the work Luther was doing to reform the church drew the ire of the enemy, and that’s what made Luther so susceptible to spiritual attack.

Luther often drove the enemy away with prayer and singing. But at Wartburg, the enemy attacked Luther’s soul so-relentlessly that the great Reformer allegedly hurled an inkwell across the room where he believed the devil to be.

It has since been suggested that the inkwell story was nothing more than a clever metaphor for Luther’s “ink” used in translating the Bible. In other words, what Luther was penning-in-ink onto the paper was the same as throwing ink at the enemy.

Still, the legend stands.

Luther was born November 10, 1483 in the town of Eisleben along a somewhat isolated stretch of what is today central Germany. He was baptized the following day, November 11, which was not uncommon in those days as infant mortality was high, and parents wanted their newborn children brought into the church fold as soon as possible.

Luther was reared in a hard time, environmentally and economically. The winters were brutally cold with the threat of disease and famine ever-present. If a man didn’t work, his family starved. Literally. Moreover, a man depended on the work of his teenage and grown sons to bring money into the household when he was no longer able.

Consequently, discipline was severe both at home and in school. It was so, out of necessity. Luther once recalled that in one morning alone he was “caned” 15 times at school for failing to have his Latin lesson prepared correctly.

As a young man, Luther initially studied law at the university in Erfurt. A demand placed on him by his father. But during a return trip to Erfurt after a quick trip home, Luther found himself exposed in the open during a terrific lightning storm in which he believed he was going to die. Praying to both God and St. Anne, he promised he would become a monk if only his life were spared. It was.

Keeping his word to God, Luther left law school for the Augustinian monastery also in Erfurt. This infuriated his father.

The die was now cast. Luther proved to be an exemplary monk; utterly devoted to monastic life. In fact, many of his fellow monks believed he was a bit extreme in his devotion; as did a few of the priests who sometimes grew tired of his incessant desire to confess.

In 1507, Luther was ordained a priest. The following year, he was sent to Wittenberg. In 1510, he made a 1,000-mile pilgrimage to Rome, and therein – after witnessing the sale of “indulgences’ and the worship of “holy relics” – began the great questions and stirrings of reform.

Luther’s 95 theses followed in 1517. He defended himself at Augsburg in 1518. He was excommunicated in 1521, the same year he was summoned to appear before the Diet at Worms, refused to recant, and then whisked away to Wartburg Castle. He returned to Wittenburg in 1522. By that time, the Protestant Reformation was in full swing. The world was changing.

Luther once said, “I would never have thought that such a storm would rise from Rome over one simple scrap of paper.”

In 1525, Luther married former nun Katharina von Bora. Together they had six children, four of whom lived until adulthood, and they raised another four orphans.

Luther was completely devoted to Katharina and his children. He loved life. He loved celebrations, feasting, and beer. Like many German women of the day, Katharina tended a garden, operated a brewery, and was always cooking and serving vast amounts of food for the many guests welcomed into the Luther home.

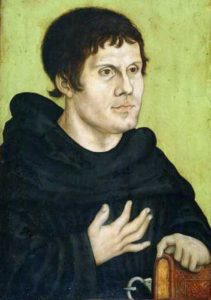

Not surprisingly, Luther had an enormous appetite and an appreciation for his wife’s beer and culinary talents. And it showed. Many of his portraits depict the great Reformer as something of a portly monk. He even self-deprecatingly referred to himself as “the fat doctor.” But his heft, as marginal as it may have been, was only acquired after middle age. As a young man, he was active, fit, and perhaps slightly underweight.

Prior to a debate In 1519, Liepzig Univ. Prof. Petrus Mosellanus described Luther as a man of “medium height with a gaunt body that has been so exhausted by studies and worries that one can almost count the bones under his skin, yet he is manly and vigorous with a high clear voice.”

Mosellanus continued, “[Luther] is full of learning and has an excellent knowledge of the Scriptures so that he can refer to facts as if they were at his fingertips. He is very courteous and friendly, and there is nothing of the stern stoic or grumpy fellow about him. He can adjust to all occasions. In a social gathering he is gay, witty, ever full of joy, always has a bright and happy face, no matter how seriously his adversaries threaten him. One can see that God’s strength is with him in his difficult undertaking.”

Luther was gregarious, passionate and profound. His writing was simple, succinct and electrifying. Spoken conversation and debate with him was stimulating to say the least, which is why the Luther home was a favorite haunt of university students and thought-leaders of the day.

Luther marveled at the world and all of God’s creation.

He once remarked, “If I knew that tomorrow was the end of the world, I would plant an apple tree today!”

One Christmas Eve, as Luther was returning home from worship services, he was struck by the unfathomable number of stars above, and was particularly awed by their shining and twinkling between the branches of the tall evergreens lining either side of the road. Inspired by the stars and trees, when he arrived home, Luther wired tiny candles around his family’s Christmas tree. He then carefully lit what is now widely held to be the first lighted Christmas tree.

By the late 1520s, various Reformation-related uprisings and wars had begun which lasted through the middle of the 17th century. This troubled Luther, who hated war and often argued against any form of violence.

Luther never stopped preaching, debating, teaching, and writing. He was a prolific writer. His writings – including the 95 theses, books, pamphlets, doctrinal works, political works, published lectures and commentaries – amounted to over well over 600 works, depending upon how the lists are organized.

Luther also wrote hymns, the most famous of which is, “A Mighty Fortress is our God.”

Luther is said to be the greatest “Father of the Protestant Reformation,” which also includes the likes of Reformation precursors John Wycliffe and John Hus, as well as Reformation fathers like John Calvin, John Knox, Ulrich Zwingli, Thomas Cranmer and many others.

Luther preached his final sermon, February 15, 1546, in his hometown of Eisleben. Within hours, he became gravely ill. He died on February 18.

Luther’s last words: “We are beggars. This is true.”

What’s in a name –

- Martin Luther was named for St. Martin of Tours as he was also baptized on the feast day of St. Martin, who was a Roman Catholic military saint who had renounced his service in the 4th-century Roman Army, and proclaimed he was a “soldier of Christ.”

- In 1934, a Southern Baptist preacher, Michael King, changed his name and that of his five-year-old son, Michael King Jr., to Martin Luther King Sr. and Martin Luther King Jr. The elder King did so following a trip to Germany in which he learned about and was inspired by the life of the great Reformer.

– W. Thomas Smith Jr. is a New York Times bestselling editor, a military analyst and military technical consultant. Visit him online at uswriter.com.